Trurl and Klapaucius are constructors, robots who have studied the art of making machines. They travel throughout the universe, selling their services to various feudal robot kings, and frequently try to one-up each other in their creations. For example, Trurl boasts that he has created a machine which can produce anything in the world that begins with the letter "N," until Klapaucius challenges it to create "nothing," at which point it begins to deconstruct the entire universe. Eventually--once Klapaucius apologizes to the machine--everything is put back to rights, but the machine can only replace the things it has disappeared which start with N, meaning never again will the universe have gruncheons, shupops, or thists.

Translating The Cyberiad from Polish must have been quite an undertaking, and Lem's translator Michael Kandel deserves recognition for somehow preserving the alliteration and wordplay that characterizes Lem's style. The stories which make up The Cyberiad swing deftly from the language of Arthurian romance to mechanical and mathematical jargon:

Trurl and Klapaucius were former pupils of the great Cerberon of Umptor, who for forty-seven years in the School of Higher Neantical Nillity expounded the General Theory of Dragons. Everyone knows that dragons don't exist. But while this simplistic formulation may satisfy the layman, it does not suffice for the scientific mind... The brilliant Cerberon, attacking the problem analytically, discovered three distinct kinds of dragon: the mythical, the chimerical, and the purely hypothetical. They were all, one might say, nonexistent, but each nonexisted in an entirely different way. And then there were the imaginary dragons, and the a-, anti- and minus-dragons (colloquially termed nots, noughts, and oughtn'ts by the experts), the minuses being the most interesting on account of the well-known dracological paradox: when two minuses hypercontiguate (an operation in the algebra of dragons corresponding roughly to simple multiplication), the product is 0.6 dragon, a real nonplusser.

The Cyberiad is a great work of science fiction because it's so clearly conversant with the theory and practice of the hard sciences--their language, their intellectual and ethical challenges--but never relies on them or allows them to dampen the imaginative impulse. It's easy to see a reflection of the absurdity of Philip K. Dick (whom Lem praised, but who in turn believed Lem to be a pseudonym of a composite of Soviet authors, amazingly). It's also a clear precursor to the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy books, of which certain elements, like the Infinite Improbability Drive that powers space travel, are basically spelled out already by Lem. All in all, The Cyberiad is funny and thoughtful--two qualities that science fiction has all too rarely.

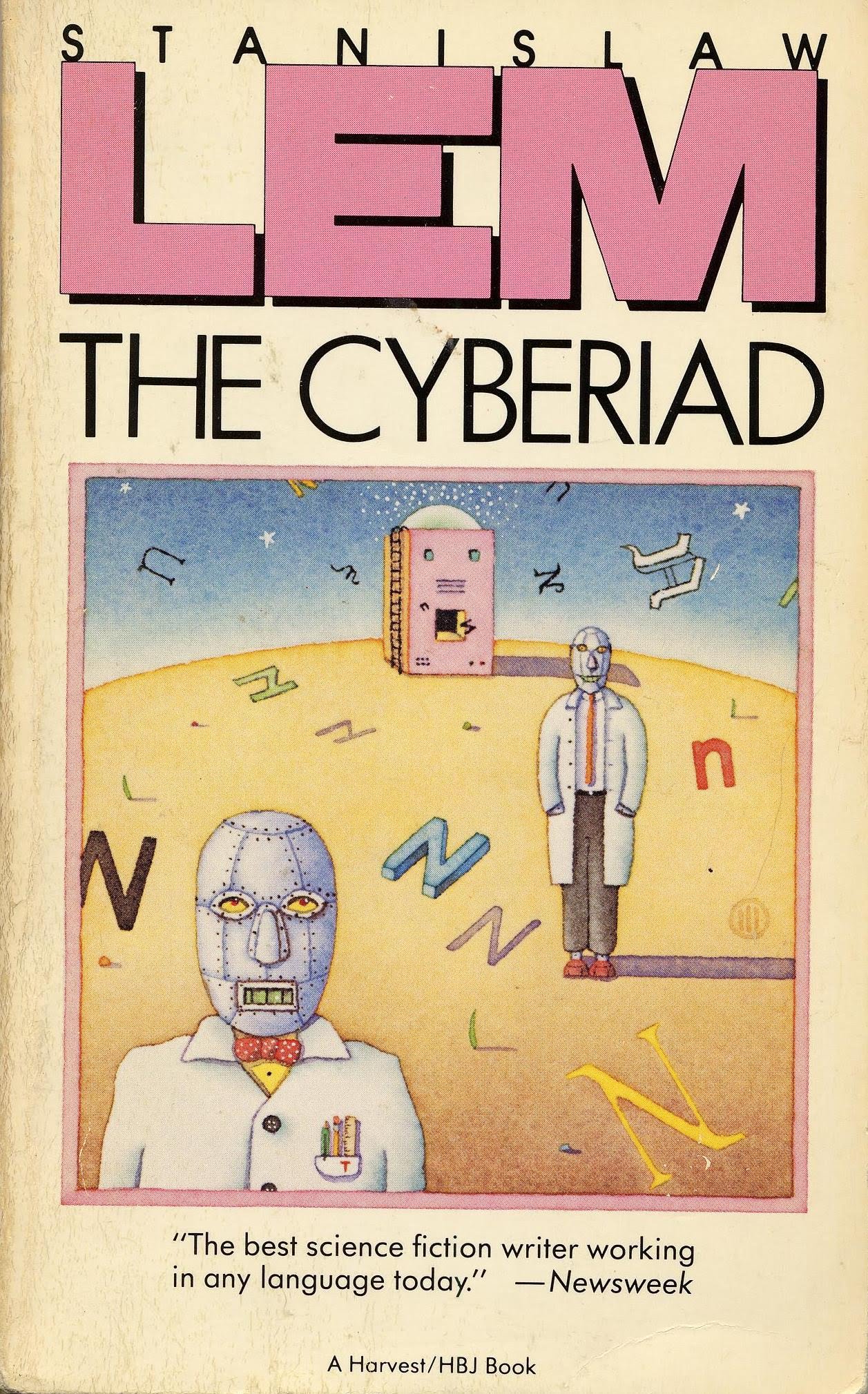

Check out this Google Doodle inspired by The Cyberiad.

No comments:

Post a Comment